Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura overview

Last updated July 18, 2025, by Marisa Wexler, MS

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, or TTP, is a blood disorder in which small blood clots form in blood vessels, leading to organ damage. TTP is considered a medical emergency and is usually fatal without treatment, but with appropriate care, most people with TTP will not die from the disease.

TTP is rare. Although its exact incidence is not known and estimates vary depending on geographic location, the disease is estimated to affect about 3.7 out of every million people each year.

Causes and risk factors

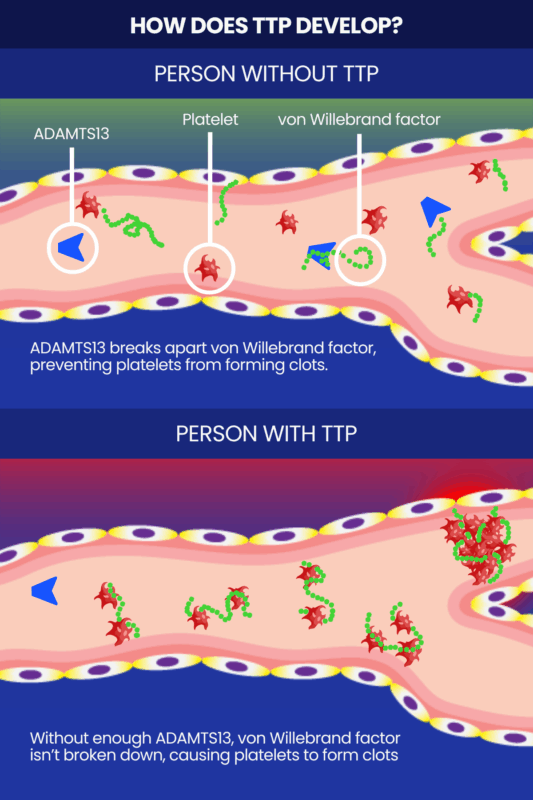

All forms of TTP are characterized by a deficiency of the ADAMTS13 enzyme. This enzyme is normally responsible for preventing platelets — small cell fragments that help form blood clots — from forming clots when they aren’t needed. ADAMTS13 specifically does so by cleaving, or breaking apart, large multimers of a clotting protein called von Willebrand factor, which otherwise induce platelets to stick together to form clots.

When the enzyme is missing or isn’t working properly, platelets start to form too many tiny clots inside blood vessels. Excessive clotting can damage organs, cause red blood cells to be destroyed, and deplete the body’s supply of platelets to the point that there aren’t enough to properly form clots when bleeding occurs elsewhere.

TTP can affect anyone, but some people are more likely to develop it than others. Risk factors for TTP include:

- being an adult

- being female

- being of African descent

- having certain infections, such as HIV

- having other medical conditions like cancer or lupus

- being obese

- being pregnant

- undergoing certain medical procedures, such as surgery or a stem cell transplant

- taking certain medicines, including chemotherapy, hormone treatments, and some types of anti-clotting medications

- taking quinine, a substance often found in tonic water and nutritional health products.

Types of TTP

There are two main types of TTP:

- acquired TTP, also known as immune-mediated TTP

- congenital TTP, also known as hereditary TTP or Upshaw-Schulman syndrome.

Both types of TTP are marked by reduced activity of the ADAMTS13 enzyme, which leads to similar health complications. The underlying cause of ADAMTS13 enzyme deficiency is different in each type, however, and treatment strategies vary somewhat.

In acquired TTP, low ADAMTS13 activity occurs because of an autoimmune attack where the immune system makes antibodies that prevent the enzyme from working correctly. Acquired TTP manifests in adulthood in 90% of the cases, and is by far the most common form, accounting for at least 95% of all TTP cases. Acquired TTP may also be further subdivided into primary or secondary, depending on whether an obvious underlying cause or disease can be identified.

Congenital TTP is caused by mutations in the gene that provides instructions to make ADAMTS13, causing the enzyme to be dysfunctional or missing. The mutations that cause congenital TTP are present from birth. This type of TTP usually causes symptoms in childhood, though there are rare cases of people who have congenital TTP but don’t start experiencing symptoms until adulthood. Congenital TTP is much rarer than the acquired form of the disease, accounting for about 3% to 5% of all TTP cases.

Symptoms

TTP symptoms can arise suddenly and progress quickly. They are driven by the excessive formation of blood clots, thrombocytopenia (low platelet counts), and hemolytic anemia — low red blood cell counts driven by red blood cell destruction. Any attack of TTP symptoms is a medical emergency that requires prompt treatment. If a patient experiences a new attack after having achieved remission from a previous episode, it is known as a TTP relapse.

Possible TTP symptoms include:

- small, flat red spots under the skin, known as petechiae

- larger red, purple, or brownish-yellow spots on the skin, called purpura

- paleness or jaundice (yellow discoloration of the skin and eyes)

- weakness and fatigue

- abnormally heavy or prolonged bleeding

- fever and/or chills

- rapid or irregular heartbeat

- shortness of breath

- headache

- confusion or other changes in mental status

- difficulty speaking

- vision changes, such as blurred or double vision

- reduced urine output and/or blood in urine

- nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and/or abdominal pain.

Potential complications

TTP can also cause a range of serious and life-threatening complications. These may include:

- seizures

- brain damage

- coma

- stroke

- heart attack

- kidney failure

- pregnancy loss.

Diagnosis

The process to establish a TTP diagnosis typically begins with a medical exam and a review of the patient’s medical and family history. If TTP is suspected, then a blood test can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

The main blood test used in the diagnosis of TTP is an assay that measures the activity of the ADAMTS13 enzyme. If the enzyme’s activity is lower than 10% of normal, then a TTP diagnosis can usually be made. This type of testing can also help distinguish TTP from other conditions with similar symptoms, such as hemolytic uremic syndrome. However, low ADAMTS13 enzyme activity can also rarely occur in people who have severe infections or cancer, so additional tests to rule out those conditions may be needed to fully confirm the diagnosis.

Measuring ADAMTS13 activity can help diagnose TTP, but can’t be used to identify the specific type of TTP a person has. Additional blood tests looking for antibodies against ADAMTS13 are needed to distinguish the two main types of TTP. If anti-ADAMTS13 antibodies are present, then the person has acquired TTP; if not, then the person likely has congenital TTP. Genetic testing to look for disease-causing mutations can also be used to confirm the diagnosis of congenital TTP.

Besides assessing ADAMTS13 activity and looking for disease-causing antibodies and mutations, a range of other diagnostic tests may be used to help diagnose TTP and assess how the disease is affecting certain organs. These may include:

- a complete blood count, which measures the number of platelets and blood cells

- a peripheral blood smear, which can be used to look for signs of hemolytic anemia such as schistocytes (red blood cell fragments)

- tests assessing the levels of bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase, high levels of which are indicative of red blood cell destruction

- kidney function tests.

It’s important to diagnose and treat TTP as quickly as possible to prevent serious complications. If TTP is suspected, treatment may be started before diagnostic results are available in some cases.

Treatment options

TTP is not curable, but several types of TTP treatment are available that can help manage the disease. These include:

- plasma exchange, a medical procedure that removes and replaces a patient’s plasma (the non-cellular part of blood) with healthy plasma from a donor

- corticosteroids, which are powerful anti-inflammatory and immune-suppressing medicines that can help reduce the production of antibodies that drive acquired TTP

- rituximab and other immunosuppressive therapies that can also lower antibody production in acquired TTP

- Cablivi (caplacizumab-yhdp), an approved therapy for acquired TTP that works to prevent the formation of tiny blood clots

- Adzynma (ADAMTS13, recombinant-krhn), an approved enzyme replacement therapy for congenital TTP that works by providing a lab-made version of ADAMTS13 to patients

- plasma infusions

- splenectomy, or surgery to remove the spleen — a major site of antibody production in acquired TTP.

Current guidelines recommend that a combination of plasma exchange and corticosteroids be used to manage acute events (first episode and relapses) in patients with acquired TTP. Rituximab and Cablivi may also be given alongside these therapies.

Guidelines also recommend that people with TTP receive prophylactic (preventive) treatment to reduce the risk of relapses. This may include:

- rituximab for acquired TTP

- Adzynma, or plasma infusions if Adzynma is not available, for congenital TTP.

People living with TTP also may benefit from supportive care to manage specific conditions associated with TTP or to prevent certain complications, as well as from emotional and psychological support.

Outlook and prognosis

TTP life expectancy depends largely on whether or not patients receive appropriate treatment. If TTP is left untreated, it is fatal in 9 out of 10 cases. But treatment can radically improve TTP prognosis: with treatment, it is estimated that about 1 or 2 out of every 10 people with TTP will die from the disease.

The risk of mortality is lowest when treatment is started as soon as possible. Prophylactic treatment to reduce the risk of future relapses can also help minimize the risk of life-threatening TTP complications.

Regular monitoring can also help minimize the risk of serious complications from TTP, as sometimes a decrease in ADAMTS13 enzyme activity can be detected before symptoms appear, allowing treatment to be given early.

Bleeding Disorders News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Recent Posts

- African ancestry linked to 50% higher iTTP relapse risk after rituximab

- Seeing my rare disease highlighted on TV brings validation and hope

- Managing anxiety levels may improve quality of life for adults with ITP: Study

- Many types of von Willebrand disease may be underdiagnosed: Study

- Add-on Cablivi improves treatment for iTTP patients, study finds