Platelet function test may better gauge bleeding danger in ITP

Reduced platelet activity linked to symptoms, treatment response in study

Written by |

An assessment of platelet function, rather than platelet counts alone, may better reflect bleeding severity and treatment response in people with immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), a study suggests.

Platelet counts alone were insufficient to identify ITP patients with or without bleeding symptoms, the data show.

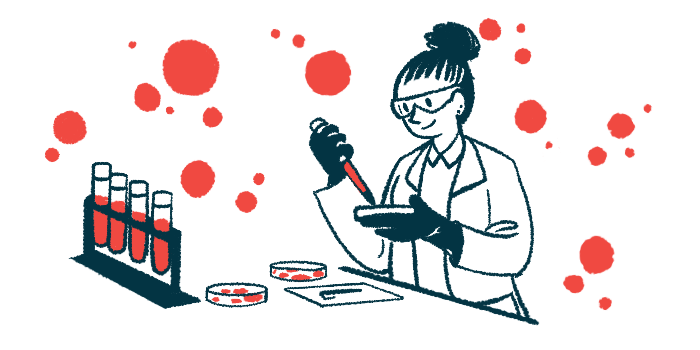

Platelet function was evaluated by measuring levels of activation markers in platelets isolated from patient blood samples following stimulation with an agent that mimics a natural platelet activator.

“This highlights the importance of including functional platelet assessments when evaluating bleeding severity,” the researchers wrote. This “could offer a promising tool for improved diagnosis, prognosis, and individualized patient management.”

The study, “A design for an efficient functional panel that determines platelet exhaustion levels to differentiate responder and non-responder ITP patients,” was published in Scientific Reports.

How ITP affects platelets and bleeding symptoms

ITP is a rare autoimmune disorder marked by low levels of platelets, the cell fragments that help blood clot, resulting in an increased risk of bleeding.

Most ITP treatment options aim to maintain platelet counts and manage bleeding risks by preventing platelets from being destroyed by the immune system or by boosting platelet production. However, bleeding severity in ITP does not always coincide with platelet counts, which can complicate treatment decisions.

Instead, bleeding severity in ITP has been linked to platelet exhaustion — when the function of the platelets themselves is impaired, even when platelet counts are adequate.

“Determining if this functional exhaustion is linked to disease activity or treatment response continues to be a significant gap in ITP research,” wrote a team led by scientists in Iran who assessed the health of platelets collected from 28 people with chronic ITP (low platelet counts for at least one year) and 20 healthy individuals.

Most of the people, ages 10-40, were female (60.7%), and more than half reported a history of bleeding (64%). Less than half (42.8%) were on second-line thrombopoietin receptor agonists (medicines that boost platelet counts). About one-fourth each were receiving first-line immunosuppressing corticosteroids (28.6%) or no treatment (28.6%).

Platelet health was assessed by measuring the levels of platelet activation markers after exposure to PMA, a molecule that mimics a naturally occurring platelet activator. Markers included P-selectin protein levels, the binding of the PAC-1 protein, and reactive oxygen species, or molecules containing oxygen generated from normal cellular metabolism.

Compared with healthy controls, the platelet response to PMA was significantly lower in ITP patients across all three markers, indicating reduced platelet activation. Patients’ platelet counts also correlated with these markers in response to PMA.

Platelet responsiveness to PMA was greater among those with platelet counts above 30 × 103 per microliter, a level considered an important cutoff point in ITP management, the team noted.

Functional testing showed high accuracy in grouping patients

In an adjusted statistical analysis, measuring these marker levels in response to PMA could accurately distinguish patients with platelet counts higher or lower than the cutoff, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.973. AUC measures a model’s ability to distinguish between two groups, with values ranging from 0.5 to 1, where higher values indicate greater accuracy.

Platelet counts did not differ between patients who showed no signs of bleeding and those with minor bleeds, such as bruising or occasional nosebleeds. Even so, platelet responsiveness to PMA was lower among those with bleeding symptoms. Based on marker levels, the AUC to distinguish patients with and without bleeding symptoms was 0.85.

The team then divided the participants into two groups based on treatment response. Responders were defined as those with a platelet count at or above the cutoff, or at least a twofold increase in counts from the start of therapy, and no bleeds. Non-responders had platelet counts lower than the cutoff, a less than twofold increase in counts, or had bleeding symptoms.

Similarly, platelet responsiveness to PMA was significantly lower among non-responders than responders. Based on marker levels, the AUC to distinguish between responders and non-responders was 0.938.

“This multifactor panel accurately reflects platelet functional state while helping to distinguish between responder and non-responder patients,” the scientists wrote. “Future studies involving a wider ITP patient population could be much appreciated to provide a better balance between different categories of patients.”