New ‘needle in the haystack’ antibody-based therapies target ITP

Study: One helped preserve platelet levels in mouse model of bleeding disorder

Written by |

Researchers have developed two novel antibody-based therapies that may be used to treat antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases such as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to a study.

In a mouse model of ITP, one of the new therapies was shown to help preserve levels of platelets, the cell fragments that help blood clot and are attacked by the immune system in ITP.

The study, “Preclinical assessment of two FcγRI-specific antibodies that competitively inhibit immune complex-FcγRI binding to suppress autoimmune responses,” was published in Nature Communications.

Antibodies mistakenly target healthy tissues in autoimmune diseases like ITP

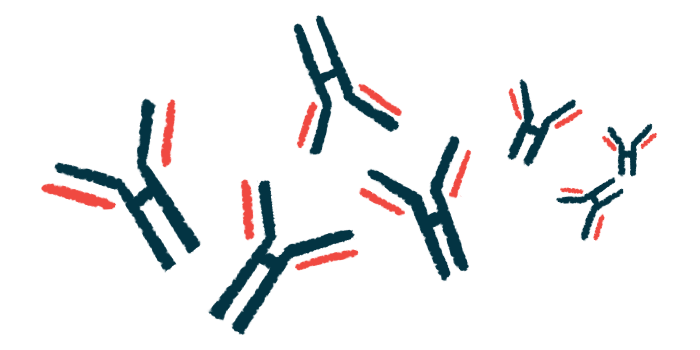

Antibodies are proteins made by the immune system to help fight infections. Antibodies are highly effective molecular weapons — a given antibody can bind to its specific target with extreme precision, marking the target for destruction. However, in autoimmune diseases like ITP, the immune system mistakenly produces antibodies that target the body’s own healthy tissues, resulting in disease.

One of the main ways antibodies kill their targets is by signaling immune cells to go on the attack. Antibodies that have bound to their target can signal to immune cells through a specific protein receptor called FcγRI, which is found on immune cells. Autoimmune diseases, such as ITP, are typically characterized by the overactivation of the FcγRI receptor, which helps drive an overall inflammatory state within the body. As such, blocking this receptor is seen as a promising strategy for controlling autoimmune diseases.

In this study, researchers devised a way to stop this antibody-driven inflammatory process — by using even more antibodies.

The significant reduction in [immune cell]-platelet interactions in [cell experiments] and the effective reduction of platelet clearance in [mouse experiments] further highlights the therapeutic potential of C01 and C04.

They engineered two antibodies, dubbed C01 and C04, that can bind to the FcγRI receptor itself. These antibodies do not activate the receptor, which means they have minimal risk of aggravating inflammation. They block the receptor from interacting with other antibodies, including the self-targeting antibodies that drive autoimmune diseases like ITP.

“I think we found the needle in the haystack, after searching over a decade, and thanks to a true team effort,” Jeanette Leusen, PhD, principal investigator of the study at University Medical Center Utrecht in the Netherlands, said in a university news story. “Each research partner contributed a critical piece, from antibody discovery and structure determination to patient sample testing and preclinical models. Only together could we bring this to fruition. These antibodies not only provide a unique tool for studying FcγRI biology, but also hold promise as therapeutic candidates in autoimmune and infectious diseases.”

In cell experiments, the researchers demonstrated that their new antibody therapies could block the binding of platelets to immune cells from people with ITP. The researchers then tested C01, which showed better binding affinity in the cell experiments, in a mouse model of ITP. Results showed mice treated with the antibody therapy retained higher platelet counts than mice given a sham treatment (49.5% vs. 29%).

“The significant reduction in [immune cell]-platelet interactions in [cell experiments] and the effective reduction of platelet clearance in [mouse experiments] further highlights the therapeutic potential of C01 and C04,” the researchers wrote.